I stopped by the library today after the gym to pick up a few DVDs. There in the lobby was a display that read, "Have you read a banned book lately?" Interested enough, I stopped to browse the titles. Amidst the children's books containing war and violence and the middle school books containing sexual content and racism there it was: The Bible. I would have thought that odd, except in one of my graduate school classes we are currently studying the history of the technology of the book. In a recent case study on how the print culture we live in came to be, I have been focusing in on censorship in book history and I came across a very interesting book:

A Universal History of the Destruction of Books : From Ancient Sumer to Modern-day Iraq by Fernando Báez. This source not only examines all the ways that books come to be lost, damaged or destroyed, it also gives an overview of major events in the making of books as we have come to know them. The professor in my graduate class describes the book as just one part of a long-term shift from oral to print culture. Consider these revolutionary steps in the development of all that print we rely on today:

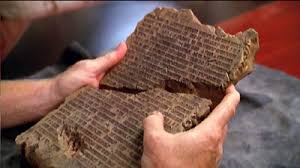

- Speaking to Writing: If the earliest

human ancestor Homo habilis, lived 2.5 million years ago, and Homo

sapiens sapiens developed writing a few thousand years ago, that means that less than 1% of humanity’s total existence occurred during written history! After the appearance of writing came the alphabet, a complete transformation of reading/writing, because even the most complex though processes could now be converted into visible signs. By the fifth century in Greece, written culture began to dominate spoken culture, though people still generally read aloud.

- Developing Writing Materials: Out of writing came the need for something portable to write on, which first appeared in Sumer (once Mesopotamia, now southern Iraq) made of fragile

clay. Then papyrus scrolls became the medium that the first Egyptian documents

and books were written on, used since 2000 BCE. Parchment and vellum (both made from animal skins) were then used, and silk and paper making developed in China.

- The Book Triumphs: Archaeological discoveries show Christian communities trading rolls of papyrus for the codex, the folded book form we recognize today, because of the low cost of vellum and the portability and durability of the book versus scrolls. Biblical texts of the second century were codices, and by third and fourth centuries almost all written texts were codices.

- Prominence and Proliferation of Print: Perhaps the most significant step in the development of printing was Gutenberg's advancement of movable type. This allowed for the reproduction of books at a level unmatched by manuscript copy and allowed for wider spread of ideas and information as books became cheaper and more accessible. Advances during the Industrial Revolution also dramatically increased production speed. The publishing industry flourished worldwide.

- New Digital Revolution: In our modern world of computers, smartphones and the Internet, the book is not simply a physical object anymore. Books today can use audiovisual, printed or electronic means to represent language. Readers today have access to a diverse range of texts through a variety of different media.

That's the basic story of how we came to have a print culture. Who knew a book about book destruction could teach so much about book history? But as Baez points out, ever since there has been production of texts, there have been attempts to control them, everything from removal of certain titles from library shelves, to purposeful and strategic human destruction of books, libraries and national repositories.

His ideas as to why books are purposely destroyed are important to understanding the concept of censorship. According to Baez, books are not destroyed because they are hated as physical objects, but rather as an attempt to “facilitate control of an individual or a society.” Texts are destroyed by those resolute in their own absolute worldview, so that when something or someone does not conform to that point of view, official censorship occurs because any difference of opinion is considered rebellion. This begins to explain the causes, justifications and objectives of censorship: to intimidate, diminish, and ultimately erase resistance.

With that in mind, we can see why something as ordinary today as an English Bible was seen as a threat to the established order and resulted in brutal censorship. Christianity itself quickly grew from a sect of rebels into an organized religion less tolerant of divergent viewpoints. As the power and authority of the Catholic Church became established throughout the Middle Ages, church leaders detected in others' literature and philosophy the source of numerous heresies, and if they could not tolerate an author's ideas they destroyed his books as a means to combat heresy. Many "members of any sect unwilling to accept the authority of the church” were burned along with their books. Voices like that of William Tyndale emerged to confront Catholic hypocrisy and encourage open reading of the Bible, which at that time was read only in Latin and limited to the clergy. Due to the threat of persecution, Tyndale worked from Germany while much of his printed translation works were smuggled into England, though sometimes intercepted and burned. Like many other authors and publishers of books considered to be heretical, Tyndale was ultimately sentenced to death for his work. In October 1536, Tyndale was tied to the stake, strangled by hanging, then burned. His legacy endures as a martyr for being one of the first to translate the Bible into English from its original languages.

It's no wonder we have come to live in a world surrounded by texts. Seeing that Bible on the banned book shelf to me proves the lasting effectiveness of printed ideas despite repeated attempts to censor them. Look at the continued popularity of the Bible as a product of mass-produced print culture today. The last I checked, it's still on the bestseller list.

Source:

Báez, Fernando. A Universal History of the Destruction of Books : From Ancient Sumer to Modern-day Iraq. New York: Atlas & Co., 2008. Print.

1. Social Interaction- I like to engage in conversations with friends, other users, and with the creators of the content.

1. Social Interaction- I like to engage in conversations with friends, other users, and with the creators of the content. 5. Community contribution- Notes and annotations reflect current knowledge and trends while enriching the context. My own contributions allow me yet another layer of interaction with the text.

5. Community contribution- Notes and annotations reflect current knowledge and trends while enriching the context. My own contributions allow me yet another layer of interaction with the text.